Commissioned by the State of New York for the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City (Queens), the New York State Pavilion was the largest in the fair and is one of the few structures from the fair to remain standing today. The Pavilion represents a unique building type—a promotional fair structure—from a period when monumental Modern structures like Lincoln Center, E.D. Stone’s U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, Kahn’s Kimball Art Museum and Saarinen’s terminals were eschewing the dominant forms of the previous decade. “Bringing together classical temple, Roman Coliseum and circus tent,” the Pavilion project reinforced Philip Johnson’s break from a strict Miesian vocabulary.

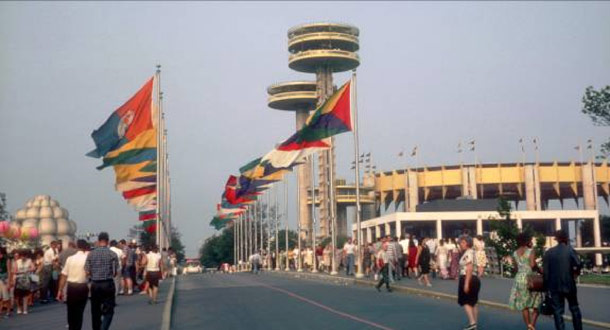

While the New York State building at the 1939 fair was a waterfront amphitheater, for the 1964 fair Gov. Nelson A. Rockefeller hired Philip Johnson to design a three-part pavilion comprised of a circular theater—”Theaterama”—showing a film about the state, a giant open-air assembly hall, and three towers, one of which gave visitors the highest point from which to view the fairgrounds. Johnson worked closely with the engineer Lev Zetlin. Thompson-Starret Construction was the contractor, with the Nicholson Company as structural engineers.

The exterior of the theater was decorated with large works by contemporary artists, among them a cartoon frame by Roy Lichtenstein, a car parts sculpture by John Chamberlain and a portrait of “Most Wanted” criminals by Andy Warhol, which was removed because of objections by fair officials. The theater was dwarfed by the adjacent assembly hall, which was 250 feet by 320 feet and elliptical in plan. A roof of multicolored plexiglass panels suspended on cables about 100 feet in the air earned the Pavilion the name “Tent of Tomorrow.” The cables stretched between a structure of riveted steel bracing held aloft by 16 concrete pylons. An oculus at the center of the roof panels recalled the Pantheon in Rome. The columns were continuously poured in five days using the slipform method. The floor of the assembly hall—and its chief attraction—was a 130 feet by 166 feet reproduction of a Texaco road map of New York State made of 567 terrazzo panels, with Texaco stations helpfully marked.

The three towers—an 228-ft observation platform, a lower pavilion where refreshments were served and a mid-range tower used as a lounge for visiting dignitaries—were reached by glass-enclosed exterior elevators called “sky-streaks,” some of the earliest of this type to be used. The pavilion’s elements were disparate in form—chunky theater; vast open hall; tall, slender towers—and in detailing-no-nonsense concrete; seemingly flimsy plexiglass; and vigorous riveted steel. The result was a structure that had the appropriately gay, borderline garish character of a fair pavilion, plus monumental scale. The New York State Pavilion received unanimous praise during the fair, including a NY AIA Excellence in Design award honorable mention. The New York State Pavilion reflects the mood of prosperity and achievement felt not only by the fair organizers, but generally across the country during the early 1960s.

In 1965 a committee appointed by mayor Wagner proposed retaining some of the fair structures, but not the NY State Pavilion. The Mayor and Robert Moses ultimately came out in favor of exempting the pavilion, which cost $11 million to build, from demolition. It was ‘”a natural tourist attraction,'” said Moses.

Unfortunately, time has not been kind to the pavilion. Under the jurisdiction of the New York City Parks Department the site has lingered in obscurity and neglect for 45 years. The steel structure has rusted considerably, the sky-streak elevators were dismantled due to precarious conditions and the terrazzo floor has been disintegrating from exposure and lack of maintenance. The World Monument Fund’s Watch List included the New York State Pavilion in its 2008 list of 100 most endangered sites.

In 2009, World Monuments Fund with support from New York City Parks and Recreation, nominated the Pavilion for inclusion in the State Register of Historic Places. In September 2009 DOCOMOMO New York/Tri-State sent a letter of support for the listing to the State Historic Preservation Office in Albany. The Historic Districts Council, New York Landmarks Conservancy, Queens Historical Society, Flushing Meadows-Corona Park World’s Fair Association and Bill Young’s New York World’s Fair 64 group, among others, also advocated the site’s listing. On September 15, 2009, New York State Historic Preservation Office designated the New York State Pavilion as a state landmark. It is hoped by all parties that the designation will open up avenues for state, federal or private grants to begin much needed preservation work.

—Hänsel Hernandez Navarro

November 2009 Update:

On two weekends in October and November current students and alumni of Columbia University’s Historic Preservation program along with city Parks Department workers and friends of the pavilion came together with garden tools, plastic bags and markers to weed out decades of moss, roots and wild plants that have wreaked havoc on the terrazzo. Loose pieces of terrazzo, along with plastic road map markers and letters, were saved, documented and stored in plastic bags for future reference. The effort was organized by the New York City Parks Department, which has plans to further conserve the “map.” Its plan is to bury it—a layer of sand, followed by a geo-textile and then gravel—to ensure that the fragile historic fabric will be protected from exposure and biological intrusions while the Department develops a conservation master plan for the site.